|

| Lloyd Loar |

This was all done despite the fact that he only worked for Gibson for five years.

Not only was Loar a luthier, he was also one of the first sound engineers and he was a performer. He paved the way for the archtop guitar and mandolin to be built in a similar fashion to the violin.

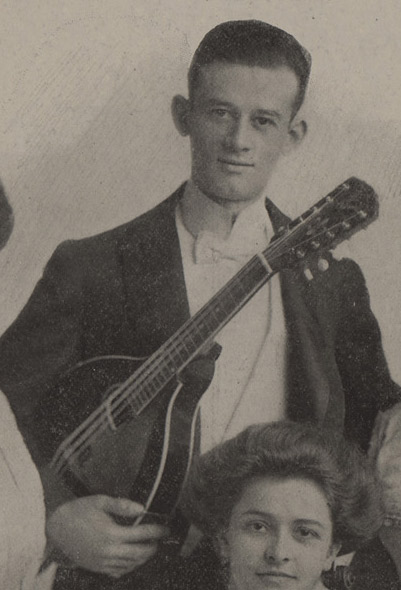

Loar had studied music while in high school and went on to attend the Oberlin Conservatory where he became proficient in mandolin, mandola, mandolin cello, violin, viola and piano performance.

In 1918 he worked as an entertainer for the troops during the war. While in Europe he studied at the Conservatory of Paris. Later he attended the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. Due to illness while in the service, he was honorably discharged within a year.

If you see vintage Gibson mandolin advertisements many of these will show a mandolin orchestra know as the Fisher-Shipp Concert Company. The players used Gibson instruments in their performances.

Loar was a member of this consortium and he was married to Sally Fisher-Shipp.

Perhaps the biggest take-away that Loar received for his participation was it allowed him to show Gibson that he could improve the products they were making. He showed them his ideas for mandolin and banjo construction, which led to him being hired by one of Gibson’s original and largest investor, Lewis Williams, who saw the potential in this young man. At first Loar was hired only on a six month contractual basis.

Loar had invented the Virzi Tone Producer prior to working for Gibson. This device was a spruce disc suspended from the instruments top that acted as a second soundboard. Mario Maccaferri had a similar idea with his internal resonator on the guitar he designed for Selmer.

After the six months were up, Lloyd Loar continued to work for Gibson from 1919, a year after Orville Gibson left the company, to 1924.

|

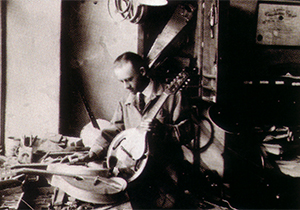

| Loar working at Gibson |

During his tenure at Gibson he was referred to as "Master Loar" by those that worked with him.

|

| Modern tap tuning |

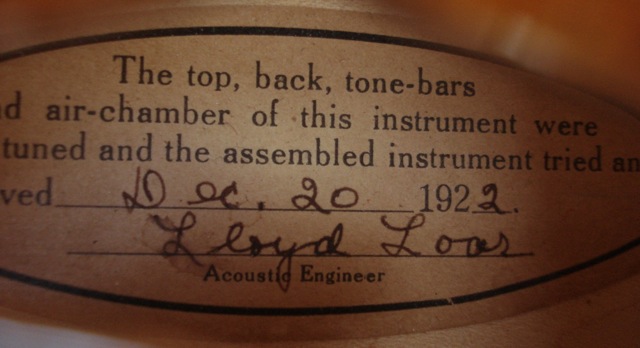

Loar spent a great deal of time and research to create this improvement for his stringed creations. He learned and spoke of Stradivari’s tuning process. Some hail this as his greatest achievement.

He would tune the wooden tops and back so the front of the instrument was a quarter tone higher than the backboard. Gibson still utilizes this principal as do many other luthiers of the day.

Due to his perfectionism regarding attuning the wood for each instrument the final result would be different for each mandolin, mandola or guitar that he made. This created a diverse and unique array of instruments.

Tap-tuning was (and is) a tedious process and under his supervision no instrument would be sold unless it was hand tuned. Only then Loar would allow his signature to be attached to the interior label.

After working at Gibson for almost five years Lloyd Loar envisioned electrified instruments and this led him to start his own company that allowed him to build electric guitars, electric violins and electric mandolins. He improved the arched the tops and backs to give them added strength as the bracing was very minimal on arched instruments.

|

| From the Siminof mandolin site |

Lloyd Loars mandolins contained tone bars. Unlike violins, the mandolins utilized two movable bars, that could be placed differently to alter the tone and provide stability. He also understood that placement of the F-holes would affect the instruments sound.

|

| Master F5 |

|

| Loar signed L-5 |

|

| 1924 Loar Gibson L-5 |

|

| Two 1924 L-5 guitars |

|

| Skip Maggoria with Gibson electric harp guitar |

This instrument is one of a kind. It had ten bass string and the usual six guitar strings. The body is carved with a scroll pattern between the two necks.

|

| Drawer on upper bout that housed the pickup (with closeup of the pickup) |

|

| Loar's personal viola - Siminof page |

|

| ViVi-Tone guitars |

|

| ViVi-Tone acoustic mandolin |

The Vivitone guitar and his other Vivitone instruments were unique because Loar took his idea for the Virzi-Tone a step father.

|

| Note the pickup "drawer" |

The backs were recessed with a rigid laminated rim. The solid wood that stood away from the rim was actually a secondary soundboard that had an additional set of F-holes.

The object was for the player to hold the Vivitone guitar or mandolin away from his body in the manner of a classical guitarist to permit the back soundboard to vibrate. These guitars featured tone bars and backs and tops that were hand tuned. The F-holes were strategically placed for maximum sound projection and a secondary set of F-holes were carved into the guitars back.

|

| ViVi-Tone Electric Violin |

Loar produced a Vivtone pear-shaped electric mandolin and an electric violin that had no back or sides. The electronic pick was house it a rectangular piece of wood that was parallel to the instruments body.

|

| ViviTone solid electric Tenor guitar |

|

| 1930's ViviTone Electric guitar |

A strip of metal ran the length of the body and neck. All the sound came from the pickup beneath its bridge. The cord was different than modern ones. It featured two prongs and was covered in cloth wrapping.

|

| Loar Amplifer with parts |

|

| Loar speaker with paddles |

Around the same time period, radio engineer Donald Leslie took this a step further than the version Loar was utilizing. Leslie made his first speaker cabinet in 1941 as an add-on to the Hammond Organ as well as other organs.

|

| Loar's personal electric piano |

This is the same principal that both Rhodes/Fender and Wurlitzer used when they designed their electric pianos decades later.

The Depression hit the United States in 1929. Investors were hard to find. Loar’s partner Lewis Williams continued to sell Vivitone Guitars through 1940. Loar concentrated on his electrified piano but was not able to keep the dream alive. He took a job teaching music theory at Northwestern University until his death in 1943.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar